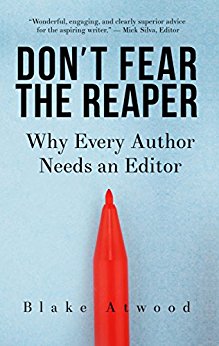

Came across a book yesterday which brought into focus something that has been bugging me for ages. Blake Atwood’s Don’t Fear the Reaper: Why every author needs an editor is squarely aimed at the new writer, especially the new Indie writer – although any writer who has an editor will be enlightened by it.

It is a seriously good book, with lots of recommendations about how authors and editors can get on better together. But it made me feel very weird.

It is a seriously good book, with lots of recommendations about how authors and editors can get on better together. But it made me feel very weird.

There are hundreds of books on Kindle right now and maybe thousands of blog posts directed at the emerging author who plans to self-publish. All this advice should help the publishing process and make the written work as good as it can be and therefore produce sales and success. Two recommendations stand out: get a professional cover designer! get a professional editor!

Cover designer, for sure. Unless you are great with Photoshop or comfortable with digital design software such as Canva, it’s not easy to get a great-looking cover. Of course there are now many automated genre cover services, where you buy a standard design and put your title and name on the front. Fair enough, as long as everyone else hasn’t chosen the same design. As time goes by and the competition on Kindle gets more intense, authors are feeling pressured to hire more and more services. Is it really making a difference to the quality of self-published books?

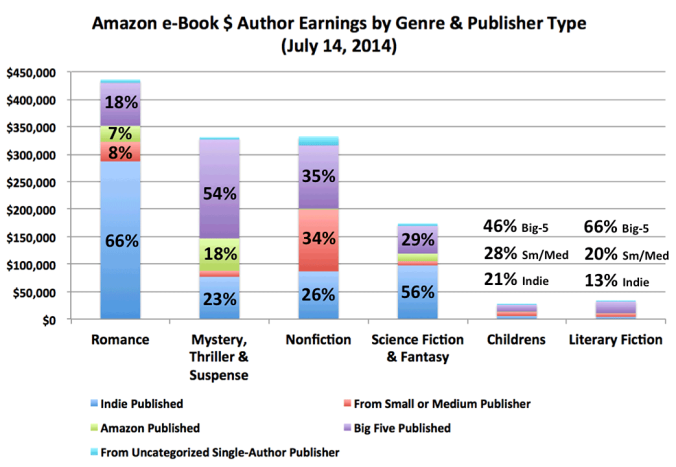

Source: Digital Book World- Team Publishing 1

Editing? It’s obvious that many new indie writers haven’t followed that piece of advice. I download and read book after book by new or unknown (to me) indie authors. It’s pretty clear that the book hasn’t been edited properly or at all. My first reaction is always irritation, even exasperation. A good premise self-destructs in an incoherent plot. Not just one or a few but scores of grammatical errors make the book unreadable. A few typos? OK. But one or two on every page? No thanks. This book joins the others in my library with the dreaded “30%” score (or less). Just couldn’t be bothered finishing it. Why does this happen?

There are three kinds of editing: developmental, which picks up on structural flaws and can result in a total rewrite; copyediting, attending closely to grammar, expression and sentence structure to make the work “correct”; and proofreading to pick up those last typos or whatever. Great! But soon the penniless hopeful discovers that an editor expects to be paid separately for each of these and some only specialize in one. Atwood is mainly a copyeditor. Editing costs seem incredible. Over a thousand dollars for just one of these edits is common.

But hang on a minute. Why aren’t the authors writing their books properly in the first place? Why can’t they edit themselves? Is it that many writers can’t in fact write? And if editors do as much on a manuscript as they claim to do, who is really the author?

I was amazed when I realized the extent to which fiction was edited. Having published around one hundred academic papers, I was used to a certain level of editorial intervention, usually to provide clarity or reduce jargon or introduce some additional analytic viewpoint in a footnote. But the idea that someone would virtually re-write your whole paper, changing your intention, re-organizing the flow of argument, removing whole sections, deleting punctuation marks and in effect taking over the construction of your work was unthinkable. You were the writer. Anyone who hired someone else to do all that made the work fraudulent. It just wasn’t your work any more. If your journal editor, having accepted your paper, chose to use an editor to make significant changes, that was an acceptable cost of being published in prestigious journals. But paying for it yourself?

The world of commercial publishing seems to take a high level of editorial intervention for granted. One of the first things in traditional publishing was to assign an editor to an author. Sometimes authors mention their editor by name, more often than not the existence of that person is completely hidden. Why? If an editor has had so much input into your work, then why isn’t that person acknowledged as a kind of author – if not a co-author, perhaps a writing associate? While it is obvious that proof-reading and minor corrections will always be required, how can the interventions of a copyeditor, let alone a developmental editor, entirely unacknowledged, be justified?

There are a set of conventions about writing which increasingly determine what will be accepted as “good” in its field. Genre fiction is one thing, literary fiction another. The hidden truth is that literary fiction is largely for people with a better education. Hundreds of Amazon reviews moan and whinge about “big words” or books being “too hard to read”. I just last night read a review which gave one star to a book because of the long words in it. The writer complained that it claimed to be a thriller but really it was a book for the “literary elite”.

A literary cocktail party at George Plimpton’s Upper East Side apartment, 1939.

Traditional publishing kept control over writing and reading by maintaining a reasonable level of quality control over what was published. And editing was key to this process. Even popular thrillers and romances were edited to maintain something like an acceptable standard of literacy. Indie publishing has thrown that out the window. Anyone can write and publish anything. This seems powerfully democratic. But is there a necessary standard for writing? Shouldn’t books be literate, even if they are not literary?

What if authors don’t agree with their editors? Blogs and forums are full of horror stories about new writers paying editors thousands of dollars only to find their recommendations unacceptable. If you have a contract with a publisher then the editors is likely to be the winner in a catfight. If the author is paying the editor directly, what then?

Source: Gramlee – see https://www.gramlee.com/blog/when-authors-and-copy-editors-disagree/

If you look closely at the advice to new writers, the people who write about how badly you need an editor are almost always editors themselves. It seems that they are right. Like Atwood, many have also published books on how to publish books. That is a good marketing strategy, especially with the bottomless pit of would-be authors filling up by the day. But new writers don’t want to spend money. They just want to write their books and publish them. Hmm. A problem: nobody wants to buy them. Read the forums where countless authors complain that nobody has bought their books. So they are encouraged to give their books away free, or almost so. What kind of product is this?

You can get ultra-cheap editing, of course. Thanks to the internet someone on the other side of the world can be your editor. So what if their English isn’t too great! They can do your “updation”, your Head-Noting and even write your blog!

It’s a minefied. I don’t want to read books which have been radically altered by an editor. I want to read what that particular author says, and to see exactly how she or he says it. It’s part of the fun of reading. If the writing is bad, so bad that I can’t enjoy the book, then I won’t buy anything from that author again. On the other hand, so many new authors write such bad books. They have awful holes in the plot or drag on too long or have blatant unexplained contradictions, and I know how much better the book could have been if someone had “edited” – in effect re-written – it.

I feel sorry for these authors. I don’t want to discourage them, so I don’t leave negative reviews. Neither does anyone else. Without an editor, or some form of independent feedback, how are authors to know their books are just not good enough? Then again, I feel sorry for their editors, if they are eventually hired. Working on badly written manuscripts, toiling over silly or boring or pompous or pointless stories and trying to make them better must be one of the most soul-destroying forms of employment imaginable – a marriage made in purgatory. [Hey, there’s a concept: a writer and an editor locked up in some horrific warehouse, in a remote derelict landscape (think Tarkovsky), going to suffer a gruesome fate if they can’t agree on final edits. If you want to develop it, let’s collaborate!]

Proofreading is another thing. Everyone needs a proof-reader. Errors creep in, typos happen and the malign influence of the spell-checker has to be remedied. I don’t know how necessary it is to hire a professional proof-reader. Maybe any two or three people who are good readers would do.

What do you think? Should editors be acknowledged, perhaps by name, when they have been hired to work on a book? Or should writers just learn to write better in the first place?

You can buy it on Amazon at the current price of $2.99 (she started at 99c) and you can download six chapters free – she will tell you where in her post.

You can buy it on Amazon at the current price of $2.99 (she started at 99c) and you can download six chapters free – she will tell you where in her post. It is a collection of previously published articles and personal memoirs, many going back to the 1970s, assembled by his wife Anne Brooksbank as a kind of memorial volume.

It is a collection of previously published articles and personal memoirs, many going back to the 1970s, assembled by his wife Anne Brooksbank as a kind of memorial volume. Australian traditional publishers don’t want authors who haven’t gone through the secret accreditation process which dominates the business. Australian agents won’t represent them. They can write books and publish them on Amazon but Amazon won’t sell the print copies in Australia. Australian booksellers stick with the traditional imprints, mostly from the Big Five international houses. Many dedicated Australian readers can’t or don’t do e-books and/or hate Amazon because they’ve been told that Amazon is the enemy.

Australian traditional publishers don’t want authors who haven’t gone through the secret accreditation process which dominates the business. Australian agents won’t represent them. They can write books and publish them on Amazon but Amazon won’t sell the print copies in Australia. Australian booksellers stick with the traditional imprints, mostly from the Big Five international houses. Many dedicated Australian readers can’t or don’t do e-books and/or hate Amazon because they’ve been told that Amazon is the enemy.

It’s hard to navigate the dangerous shoals of self-publishing. It took me the better part of a year just to get an already written story ready for the publishing process – editing, formatting, negotiations over cover (and illustrations), first round of corrections, loading and reloading files, finding and correcting mistakes, reloading files yet again —2016 was coming to an end and I really wanted to get this book out. I had already decided publishing through Amazon was the obvious way to go.

It’s hard to navigate the dangerous shoals of self-publishing. It took me the better part of a year just to get an already written story ready for the publishing process – editing, formatting, negotiations over cover (and illustrations), first round of corrections, loading and reloading files, finding and correcting mistakes, reloading files yet again —2016 was coming to an end and I really wanted to get this book out. I had already decided publishing through Amazon was the obvious way to go.