PABULUM FOR THE PEOPLE: FEUILLETON Dec 2024

A lovely comment from Andrew Blackman on my Feuilleton musings came in this week. Andrew is a literary fiction writer and blogger, a highly engaging homme de lettres, check out his reading roundup for 2024 (Andrewblackman.net).

Andrew used the word pabulum, which describes so much of what passes for literary and cultural commentary today. My brain cells lit up in that mysterious region wherever spelling is stored (what a weird cupboard of miscellanies that must be) delivering one of those sudden jolts where one thinks one has made a damnable spelling error. Hadn’t I called it “pablum”? Which was it? Google’s AI overview was unequivocal. “The correct spelling is pablum” it said.

Turns out there is a history. In the US it’s pablum, in Britain it’s pabulum, which was originally Latin for “food” or “fodder”. It was first used in English in the 17th century.

Pabulum did not always have a negative connotation. In botany it can still be used to describe nutrients in a state suitable for absorption by plants. In religious circles it describes material appropriate for presentation in a sermon. But in common contemporary usage it is something offered for consumption which is simplistic, bland, or insipid, intended to offend no one.

Herman Hesse, in his scathing assessment of the Feiulleton, probably was unaware of the product. Horkheimer and Adorno, those early titans of cultural critique, would probably have known it, but maybe the modern connotation had not yet developed. It certainly would have suited their views on the culture industry. “The consumers are the workers and employees, the farmers and lower middle class. Capitalist production so confined them, body and soul, that they fall helpless victims to what is offered to them”. [Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, New York, Continuum, 1994 p. 142.*

I was intrigued by the idea that what was once a useful descriptor for a valuable aspect of nutrition had been downgraded to a neat way of passing scathing remarks about other people’s cultural production and consumption. So what was pablum’s story?

If you start with Youtube’s definition, you won’t be much the wiser. The instant AI translation that appears in the black box is particularly confusing since it spells the word “Babylon”. I don’t think this has anything to do with reggae culture but it’s a serendipitous fit since “Babylon” is the term for western capitalist culture in Jamaica. Pab(u)lum is Babylon’s product, so to speak.

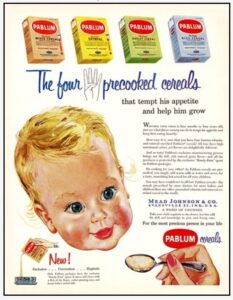

Further exploration revealed that the common US spelling for the word arose from the name of a pre-cooked and fortified baby cereal developed in the late 1920s by three Canadian paediatricians. PABLUM was designed to combat nutritional deficiencies, particularly rickets, in children, and contained a great array of very good things. These included wheat meal, oatmeal, cornmeal, bone meal, dried brewers’ yeast, powdered alfalfa leaf, and iron. It was one of the first commercial uses of additives to support human nutrition in manufactured foods. Babies needed this food because their diets were so appallingly limited in eras of food shortage notably during the Depression.

Horkheimer and Adorno were writing at a time when Pablum was well-established in the US market, but perhaps they weren’t all that familiar with baby food.

The negative connotations arose from the fact that the cereal was pre-cooked and easy to digest. From that point of view, then, the Feuilleton might indeed be usefully described as “pab(u)lum”: it contains plenty of valuable stuff, but in a simple form suitable for the unsophisticated. Is that necessarily a bad thing?

*(The book was first published as Philosophische Fragmente in New York in 1944, by the Institute for Social Research. A revised version was published as Dialektik der Aufklärung in Amsterdam by Querido in 1947).

COCKTAIL OF THE POST:

In the process of thinking about how to use the Feuilleton as a means of offering digressions on the theme of contemporary culture, I decided that each Feuilleton deserved its own cocktail. I will be writing more on the cocktail shortly. However to launch the series I offer here this recommendation:

Malted Brandy Alexander:

Everyone knows that brandy is good for you. When I was growing up there was always a bottle of brandy in the house: it was called “medicinal” and people certainly felt better when they drank it. I was a very sickly baby and my father attributes my survival to the several drops of brandy he added to the goat’s milk on which I subsisted for many months of my early life.

Malt, and malt products, likewise are well known for their health benefits. Exactly what these are is not scientifically proven, but there are no doubt very valuable vitamins and minerals in malt, being derived from malted barley, a whole grain with natural enzymes. There are various malt products suitable for this cocktail. Thick malt syrup can be drizzled over the cream, or a product such as Ovaltine can be dusted over the tip instead of, or along with, the grated nutmeg. This will give a crunchy quality to the drink which is not to everyone’s taste.

One of the earliest known printed recipes for the Alexander can be found in Hugo Ensslin’s 1916 book Recipes for Mixed Drinks. The cocktail, according to historian Barry Popik, was likely born at Hotel Rector, New York City’s premier pre-Prohibition lobster palace. The bartender there, a certain Troy Alexander, created his eponymous concoction in order to serve a white drink at a dinner celebrating Phoebe Snow. [for more information, see https://www.liquor.com/recipes/brandy-alexander/]

The cocktail graces several well-known novels of an earlier era. In Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945) Anthony Blanche, an eccentric decadent friend of Captain Charles Ryder was at the George Bar, where he ordered ‘Four Alexandra [sic] cocktails please,’ ranged them before him with a loud “Yum-yum’ which drew every eye, outraged, upon him. ‘I expect you would prefer sherry, but, my dear Charles, you are not going to have sherry. Isn’t this a delicious concoction? You don’t like it? Then, I will drink it for you. One, two, three, four, down the red lane they go. How the students stare!’…

Poor-man’s Brandy Alexander, such as my father sometimes served to my mother on a special occasion, was made with the usual brandy we had in the back of the cupboard for medicinal purposes. Once he made it with Nestle’s Condensed Milk instead of cream, which was a bit sweet, but interesting.

The use of a decent cognac lifts this recipe to great heights.

This recipe for Brandy Alexander (without the fortifications) was originally published on Liquor.com in 2011.

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 ounces cognac

- 1 ounce dark creme de cacao

- 1 ounce cream

- Garnish: grated nutmeg

Steps

- Add cognac, dark creme de cacao and cream into a shaker with ice and shake until well-chilled.

- Strain into a chilled cocktail glass or a coupe glass.

- Garnish with freshly grated nutmeg.

FOR THE FORTIFIED PABLUM SPECIAL VERSION, drizzle one or two teaspoonsful of malt extract over the top of the cream before sprinkling with nutmeg and/or Ovaltine. Slightly heating the malt extract will make it more liquid. To compensate, ensure the cream is very cold. To really ramp up the nutritional benefits, top the drink with a scoop of quality ice cream.