I have been struggling for years with a problem which has held me back from my literary destiny (ha ha). Fortunately, Joan Didion suddenly if posthumously stepped onto the dancefloor of the writers’ parlour. She died in December 2021, aged 87. Her raw diaries are about to be cooked in April. A segment of her unpublished work, consisting of journal entries addressed to her late husband John Gregory Dunne, will be published. There is a history to the discovery of these diaries and the decision to publish them without further edits but I won’t go into it here. The book titled Notes to John include reflections on her experiences as she attempts to make sense of her husband’s sudden death, her weird and frustrating relationship with her daughter Quintana Roo and her difficulties with work, alcohol, depression and anxiety. Her interactions with her psychiatrist reflect on this.

She left these diaries perfectly arranged so it is reasonable to assume she wanted them to survive and therefore to be read. Don’t we all who keep diaries secretly hope there is some enduring place for them? For many writers, especially women, diaries have been an inseparable part of their identity. Quite a few writers now publish their own diaries, or extracts from them, or cite them in their memoirs.

I know there are “issues” with Joan Didion. She is seen as conservative, pro-Republican, reliant on men, ideologically suspect. I’ve been seeing her more clearly through Lili Anolik’s book Didion and Babitz (2024) and will probably write more about it shortly. For now, though, it is something in Joan Didion’s early work that is on my mind – something I read once and then forgot about, which has just resurfaced.

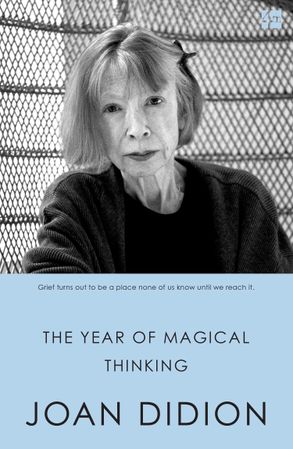

Mostly it was her book The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) which became important to me. She wrote it after the sudden death by heart attack of her husband, at a time when her adult daughter was suffering a severe illness. The atmosphere of her book enfolded me when I first began to write my own mortality memoir Regret Horizon (still unpublished). My mother died in 2008. She didn’t die suddenly but weakened slowly and defiantly until passing away in hospital at 93 after an accident with her dentures. My book turned out nothing like Didion’s: I surprised myself by writing an almost ethnographic account of my mother’s final year of life, my own mismanagement of it, and the immediate consequences of her death.

Later her book Blue Nights (2011) reflected on her life with her daughter, who was born at almost exactly the same time as my first child (in early 1966) and died in 2005 aged 39. I was still trying to draft my book. I didn’t want to go into my relationship with my own children, although that necessarily suffused the story and I couldn’t repress it altogether.

In the recent burst of pre-publicity surrounding her diaries I came across reference to something which hit me with one of those “OMG yes” moments.

Her first collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, was published in 1968. In her essay “On Keeping a Notebook” she talked about writing not as a means of recording facts but a way of capturing moments in all their specificity, giving a kind of enduring existence to the flickering and pulsing of emotion and impression before they disappeared altogether. She wrote about the need to recognize the people we used to be.

I read that essay around 1970 while trying to deal with the notebooks I had written while “in the field” doing research in First Nations communities in remote Arnhem Land, carrying out a project for a higher degree. The topic of my research was supposed to be “the women’s point of view” in an indigenous community still closely embedded in the pre-invasion way of life. I tried to do the right thing, to keep accurate accounts of behaviour and conversation, to find out what women thought about traditional marriage arrangements and social organization and struggled to find a way to write that was somehow scientific and objective and academically acceptable. Given that there were no existing examples of such a project that I knew of, I had no guidelines to follow.

I very soon discovered I could not possibly write this kind of thing. Instead, I was writing notes which were more like diaries because of the way I experienced the events I needed to write about. My two-year-old son was with me. I was a mother. There was no way around that, no “objective” position available. The things that happened as day followed day and the dry season became the wet season and I slowly learnt the indigenous language and spent most of my time with other mothers and children created a personal life for us in that community, and outside it as well. This existence seemed to have nothing to do with the “professional” persona through whom I was supposed to be demonstrating my academic and objective research capacities which was the reason for us being there in the first place.

Any anthropologist who did old-school fieldwork in those times experienced something like this, but it was particularly powerful for me, a very young woman, a mother with a small child. Moreover not long I arrived “in the field” I discovered I was pregnant with a second child, conceived just before I left Sydney where my husband was pursuing his own activities. In “researching” women’s lives in that community I became a different self. I was given an identity, with people assigned as my kinfolk and expectations of my behaviour arising from those relationships. My “fieldnotes” became more and more a diary, and I realised that the writer was neither the person living in that community in those moments, nor the person who came from a prestigious University far away in the city. The actual writer was an intermediary being who came into existence at night as the cockroaches scuttled across the concrete floor in the flickering light of a kerosene lamp and my son slept in the old caravan next door.

Time passed, my pregnancy progressed, I had to go back to Sydney for the birth.

Later, trying to make sense of this writing which was neither and both field-notes and diary, a new and different writer emerged. This person had to reflect on the embodied feelings, the conditions of daily existence, the conversations, the rituals shared, the moments remembered, an entirely discontinuous reality which now lay bizarrely in the past. It seemed almost impossible that this was the same person now writing an academic thesis in sunny Sydney, a new baby in a basket and a husband dealing with his own traumas.

What I finally wrote was very distant from the original research proposal. It turned out to be about child-bearing and child-rearing, something most professional anthropologists were completely uninterested in. It was published to almost complete silence. In the confusing times which followed, I wrote academic works. I went to a different “field”, this time with my husband and two young children, and the problem of writing and identity was even worse, capped off by the fact that my son set fire to our tent and caravan, thus incinerating eight months of fieldnotes and diaries.

Much much later my academic career was nearing its end. My mother was dying, and so was my ex-husband. I had to write about, that year and its aftermath. I wrote bits and pieces, draft after draft, various chapters, discarded, rewrote, but couldn’t bring the project to an end. I began a final edit and still didn’t like it. I needed the book to change. I didn’t know who this writer was either and didn’t like any of the versions of her who came forward as “author”.

Then suddenly I rediscovered this quote from Joan Didion’s “On Keeping a Notebook”, from the 1968 collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise, they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.”

I’d had so many bad nights but had not considered that it was those irritating people I used to be hammering at the door. These entities all seemed to have a hand in my book, toiling over paragraphs, edited out superfluities, then put more in. They were all trying to write my book. Outlook and expression and desire, indeed the very reasons for the writing, seemed to be constantly changing. All writers understand that the “author” is not the ”writer”, but what if there are several of them vying for dominance? Perhaps all “authors” suffer from MPD. Except for writers of rapid release genre fiction, who will now be the instruments of AI. But that is another topic.

I had turned it all outwards: I thought it was the real people in my life making demands on me, and I was trying to write this memoir to make amends to them. But it wasn’t them I had to make amends to, it was the old entities who had occupied the placeholder “me”. How Joan Didion, at such an early age (she would she would have been 34 in 1968), could have come to this blasting insight seems amazing. Now Joan is back in my life I am re-reading her with different ears and eyes and maybe I will find out. And if I can keep on good enough terms with those other denizen/components of the authorial entity, I will be able to finally let the book go – publish it, or let it perish.

Some recent notes on Joan Didion:

Nathan Heller. “What we get wrong about Joan Didion”. The New Yorker, 25 Jan 2021.

Karina Longworth (Substack podcast): “Lili Anolik on Joan Didion + John Wayne”. 30Jan 2025.

Cerys Davies. “Joan Didion’s diary of post-therapy notes is going to be published”. LA Times, 5 February 2025.

Daniel Lavery. “A Sneak Peek at the Upcoming and Never-Before-Read Joan Didion Diaries”. The Chantner. Substack. 18 February 2025.

Marissa Vivian. “Hemingway: What Her Words Reveal About the Ethics of Publishing her own Diary”. Substack. 8 February 2025.