BOOK REVIEW: Here One Moment: Pan Macmillan Australia 2024. 528 pages.

(This review is 2300 words long. An edited version is available on my Substack, go to:Substack.com@annettehamilton “Dissatsfied Insects”)

A few years ago, before Covid, maybe it was 2018, my partner and I sat in the modestly sized ballroom at the Carrington Hotel in Katoomba, a picturesque mountain town not far from Sydney, to hear Liane Moriarty being interviewed at the Blue Mountains Writer’s Festival. She was posed on the stage in the glary lights, neat, well-groomed, pleasant looking; and when she spoke she was articulate, thoughtful, kind and agreeable. No OTT farrago of carefully curated authorial persona here. She seemed like any attractive middle-aged well-educated woman from a middle-class Sydney suburb. White, heterosexual, “normal”.

Liking Liane Moriarty’s books was, at that time, not acceptable in prevailing literary circles. A convenient statement appeared in a 2016 online review of Truly Madly Guilty by “Wadholloway”

“I shouldn’t have undertaken to review another Liane Moriarty. She’s Sydney, I’m Melbourne. She’s popular, I prefer literary. She’s plain vanilla whitebread middle class bleeding heart first world problems, and I like my reading just a little bit grittier.”

The fact that even then she was probably the best-selling and most successful recent Australian woman writer was not of interest to legit literati.

Her latest book, Here One Moment, is an international hit, pleasing most of her readers, or those who leave reviews on Amazon at least. Ranked #23 in all Books, and #4 in Family Life Fiction (Books) it is #1 in the Amazon “Most Gifted” category.

Her readership has rocketed and she has a huge transnational presence. There are translations in over forty languages. Three of her ten novels have hit the New York Times best seller list (Big Little Lies, Nine Perfect Strangers, and Apples Never Fall) and these, as well as most of her other books, have been re-imagined for movies and/or television serialisation. Liane Moriarty is credited as producer.

Her profile in the US has been vastly enhanced by the enthusiasm of Reece Witherspoon and the appearance of Nicole Kidman in a key role in the screen adaptation of Big Little Lies.

I picked up the “buzz” around Liane’s early books. I read most of them with a certain baffled admiration. She wrote well. Her books were all set in Australia, many in suburban Sydney, and described places which I, as a mother of three children living in various suburbs at an earlier time of my life, immediately recognised. She wrote real narratives about familiar people. Her stories and the moral dilemmas behind them were complex and puzzling. She delicately peeled away the appearance of placid stability and determined respectability which so characterise the Australian urban middle class, uncertain about its own security, uneasy about its core values, stitched up around family life, unsure of the best way to negotiate the brutal competition for status and influence. Moriarty gets right inside the churning dissatisfaction which characterises the female experience of wifedom and maternity, developed in the 1950s and preserved well into the 2000s. She takes the reader into the silent region of hopes and fears beating away in the hearts of the guests at the Sunday barbecue or the cheery-if-hungover Dads sizzling sausages on the soccer field. Not really “vanilla” at all, more a chili, smoked kipper and pepperoni flavouring hidden inside what looks like cheesecake.

Just along from us sat an older couple and a younger woman. While waiting for the session to begin, we got to chatting, expressing appreciation of Liane’s work and admiration for her ability to go so carefully into such deep waters. I expressed regret that she didn’t seem to have the impact in literary circles that one might have expected. We laughed together and got on famously. I thought they would make excellent friends with common interests. When I asked hopefully if they lived in the mountains they laughed and said, no, they were Liane’s parents, and this was her very talented sister Jaclyn.

Liane appeared again at the Blue Mountains Writer’s Festival in November 2024. This time, she was a rock star. She spoke in the community hall, the largest space available to the Festival in Katoomba, on the same program as a very different Australian author-heroine with a newly published book, Gina Chick. More on her in another post. There was an air of adoration in that room. These were not middle class white bread etc etc readers, these were women and men from all kinds of backgrounds and demographics, engaged with Australia’s current literary culture. Liane spoke about her new book. Many had already purchased copies which no doubt they hoped she would later sign.

At that point I hadn’t read it. I wasn’t even sure I was going to. I have been so deep in struggle with my own memoir which seems to exist near Moriarty’s terrain, since it is about families and Sydney and women and ambition and sadness and grief. I didn’t want to feel derailed by her ability to say things clearly, I couldn’t emulate her grip on a complex narrative. I thought it might make my own book even harder to finish than it already was, so thought it might be better not to read her latest.

But after that Writer’s Festival appearance I couldn’t avoid it. I downloaded here one moment* onto my Kindle. It turns out to be a long book – in the softcover print version 528 pages. I began reading it and felt baffled again, but differently baffled. This story was even more complex than usual. Unlike most of her books, it was all over the place, and the time, literally. A welter of explanatory philosophical positions are followed by a mathematical function called Kronecker’s Delta. It’s impossible to explain just how this works but it suddenly jolted what had seemed a disjointed and often bizarrely disconnected set of characters and events into a different mind-space where she seemed to be saying something incredibly important even though I still felt I didn’t understand it.

There is some strange typographic font thing going on with her book cover. On the Australian edition the title appears without capital letters. All the reviews and listings for the book use upper case for first letters, as is usual with novels. But I think the book is good in lower case, so to speak. Without a serious and imposing font, it emphasises the qualities of the butterfly wings changing the course of history, even though it was a seagull’s wings in Lorenz’s original formulation, as Moriarty’s main character explains.

SPOILER ALERT:

Cherry, the supposed psychic who sets the events of the tale in motion, wears a particular piece of jewellery which leads to her identity being discovered by the many people affected by her predictions of the timing and reason for their deaths. These predictions are uttered seemingly for no reason on a plane bound from Hobart to Sydney. Her beautiful gold brooch is inscribed with the Kronecker Delta symbol and Cherry has worn it every day since her late husband Ned gave it to her on their first wedding anniversary. Naturally I wanted to find out more about the Kronecker Delta symbol and how this related to the theoretical and spiritual elements of the book and this took me into the realms of algebraic theory, far beyond my comfort zone. One of the characters was called Leopold, and the original Kronecker who developed the Delta symbol was also called Leopold, but I wasn’t sure how important this was.

The Kronecker Delta symbol is concerned with the way one small event can have vast consequences in its ultimate effects. ‘Could the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?’ asked the bearded man with a beatific smile …’

(p. 162 in Chapter 38). Later, Cherry tells us that she was the butterfly, although it should have been a seagull. ‘I walked through that plane squawking my predictions, flapping my wings, and my actions had consequences which had consequences which had consequences’ (Chapter 40).

It turns out that Cherry is an actuary, and hence an expert on mathematical measurement of life expectancy, as well as being the daughter of a fortune teller. Whether or not Kronecker’s symbol really has anything to do with what the book is saying, the eventual supposition or interpretation seemed to me to be: basically everything is chance. There is no meaning to it. Nobody can know how one event will lead to another. But nothing is unchangeable. People can interfere based on incorrect assumptions and things may still turn out very well. The type example of this is Timmy, who Cherry predicts will drown at the age of 7. His mother, terrified the prediction will come true, enrols him for baby swimming lessons and devotes incalculable time to making sure he is an excellent swimmer. The prediction does not come true, but instead he, his family and indeed the entire country benefit from these events and he becomes an Olympic swimmer and doubtless gold medallist. This is such a deeply Australian conclusion.

I am not quite sure but am beginning to think that Liane’s latest book is traversing some kind of meta-philosophy of Australian existence. The recent death of her much loved father seems to infuse the book from start to finish, even though she never says anything to indicate this. I could only read it as a deep engagement with life, death and meaning, common but profound existential questions which arise when a loved parent dies while the child is in middle age.

The emergent philosophy seems to be something like: efforts to understand life as the result of fate or destiny or as arising from some supernatural significance are wholly misguided. Whatever happens, happens. You can change it or not, depending on the circumstances, and you never really know how things will turn out even if you apply the best possible methods. You can calculate and have expectations, based on mathematically validated predictions: cohorts of certain kinds of people who do certain kinds of things are likely to die of heart attacks, for instance, but in any given case there is no way of knowing who will defy the expectations and who will succumb. Psychics and others can indicate possible outcomes and sometimes they might be right but if so that is an unpredictable accident. Things do often look bad, you have to be afraid, you can’t control any of it, maybe it’s dumb luck and maybe that is a mistaken concept anyway because what we think of as luck is the outcome of some Brazilian butterfly’s flapping (and I don’t mean a butt-lift, but even that could cause all kinds of outcomes).

This feels like a very Australian philosophy. It’s the kind of thing my old father would have said, in different words, before he died in 1983. It’s a stoic frame of mind, the kind of world view that accompanied the Australian experience before twentieth century late modernity took hold. It was the view that took people took through the Depression and two World Wars and long before that, in the grinding rural struggle against floods and fire and poverty, untreatable illnesses, the painful unmedicated births and cruel deaths of babies and children. This perspective survives to a degree in the literary legacy, although any contemporary recognition of the harsh settler life is muted by the awareness of what was happening on the indigenous frontier. A term for it might be Ozstoic.

Stoic philosophy has resurfaced lately in Australia. It fits the land, the place, the feelings, the increasingly unpredictable conditions, the endless circuits of wild bushfires and devastating floods that mark everyday life in most parts of Australia, urban and rural. The power goes out for days on end. People have to work out how to exist without the appliances that we have come to take for granted. Having grown up without any of them, since our family house on the Hawkesbury was not connected to electricity until the late 1960s, it’s no shock to me, but for younger people who have experienced the secure abundance of the last few decades it’s a big shock, and worse to come.

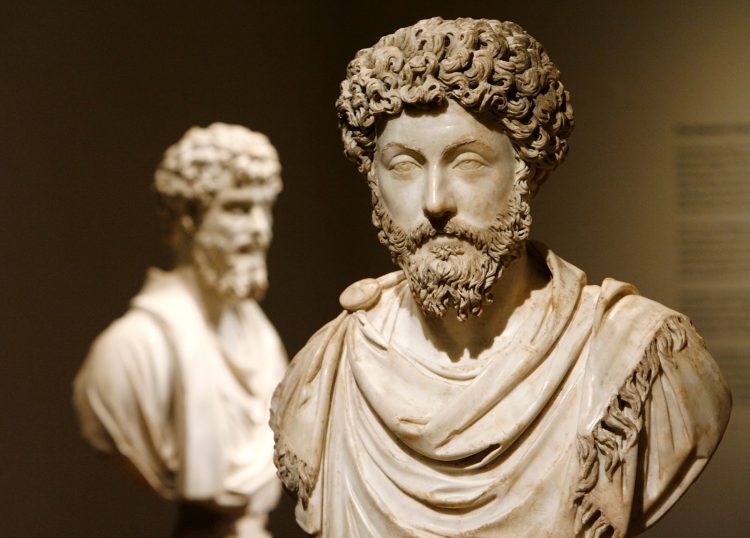

Bust of Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius (Wikimedia Commons)

We don’t need psychics on planes to tell us to take another look at how we live our lives, at what we can expect, at what we must adjust to, take into account – and to realise the extent to which it is not in our control. It feels like Liane Moriarty’s latest book is holding these realities up to our faces, and we can’t help but see them, even if we try to keep our eyes shut. Yes, anything can happen.

I couldn’t resist using the cover of Australian writer OJ Modjeska’s Gone: Catastrophe in Paradise here. The flight from Hobart to Sydney which is central to Moriarty’s book does not go down: but it could have. That would have been a very different way to end the story. Modjeska’s limpidly acute account of an actual air disaster in Tenerife in 1977 is powerfully imbued with the same awareness as appears in Moriarty’s book. A series of seemingly random events and unpredictable errors results in a horrendous outcome with hundreds of deaths, mostly of people going on holidays. Read it.